For many teachers, summer has commenced, while for others such as myself, the beginning of a school year is right around the corner. I’ve seen so many teachers on various social media sites using their summer to plan for new and exciting things they want to do the next school year – new labels, bulletin board decorations (dollar spot at Target, anyone?), teacher planners, seating arrangements, lessons, and classroom procedures .

However, I have yet to read about how teachers plan to change anything about the way they grade, or more specifically, whether or not they ever grade their gradebook. Admit it – you heart doesn’t race and your spirits don’t soar at the thought of categories, weights, and percentages (even you math teachers out there!).

I mean, sure, it’s easy to only think about which texts, units, activities, etc. you want to keep and which ones you hope to teach next year, but have you ever taken a step back and asked yourself,

Are my grades working for my students and me?”

Why do we have grades?

Before we dive into this idea, let’s consider the point of grades. Not assessments, GRADES. Upon Googling the phrase “Why do we have grades,” I noticed that on the first page of my search, the majority of the results contain an overall disdain for grades. No surprise there.

Before we dive into this idea, let’s consider the point of grades. Not assessments, GRADES. Upon Googling the phrase “Why do we have grades,” I noticed that on the first page of my search, the majority of the results contain an overall disdain for grades. No surprise there.

It wasn’t until the third page that I found an answer from the Seattle PI:

Issued up to four times throughout the school year, “letter grade” report cards detail students’ general academic performance.”

This is a good working definition. The point is to communicate a student’s academic performance.

What and to whom do grades communicate?

- Parents, who want to know how their child is performing in your class.

- Students, who want to know if their work is good enough.

- Counselors, who want to know how the student is progressing and if they need interventions.

- Higher education, who wants to know if that student is well-prepared for rigorous programs.

When speaking to my colleagues to clarify what “academic performance” is and its relation to grades, it makes many of them bristle (and perhaps you as well). Obviously academic performance looks different in every subject, and few teachers want to discuss their creative ways of measuring that.

Often the purpose of grades is unclear

We have to admit that not all teachers use grades to communicate academic performance.

- Some use them as punishment and as motivation for students to do their work and do it well.

- Some teachers assign points for showing up, writing something down (that wonderful participation grade), or offer extra credit when the original assignment wasn’t even completed.

- I had several college professors whose only grade in the gradebook was the final exam (EEK!).

I’ve seen many a gradebook with a series of points for an assignment labeled as “Homework 1/22” or something to that effect, with a score of 67%. As a student, I may remember what my homework for January 22 was, but as a parent, probably not.

Therefore, in this instance, I have no idea if my darling child only knows 67% of the material, did 67% of the work, lost points for late completion, or if there are other factors involved with that assignment.

How is this grade detailing the student’s academic performance?

What are your grading priorities?

When evaluating your own grading methods, consider these 5 questions:

What do your grading policies reveal about your students – and yourself?

More thoughts to consider (especially if you teach at the middle and high school level):

- If I gave a student an F – or even if I chose to believe that they earned an F – what does that communicate to that student about their level of mastery?

- How will that F motivate him or her to be a better student?

- How will giving him or her a zero – which, mathematically, is a score that no student can truly recover from – lead to more positive behaviors? (Think about averages and how a zero brings that down)

With that in mind:

- If a student turns in an assignment a week late, but it’s completed perfectly, will taking off five points for every day it’s late reflect their level of mastery?

- Will that penalty encourage that student to be more conscientious with his or her deadlines?

- When we look at that same student’s grades in the gradebook, will we see a D or F because of lack of understanding or a lack of time management?

- Should we really be assessing students based on their ability to meet deadlines?

- If not, where should we include that in our gradebook?

Finally,

- Think about how many of your students chronically turn in late assignments?

- Make a hypothesis as to how many of those students eventually just stopped turning anything in because the late penalty dropped their grade so low that it didn’t matter?

Practice makes perfect, but failing at practice means a failing grade?

Are your students being punished for each time they practice a skill – whether it’s at school or at home?

We wouldn’t unfairly judge someone if they fall the first time they put on roller skates. So why would we unfairly penalize a student when they first try a new skill? Why would our classwork and homework grade be worth more than a summative assessment?

While I don’t want to dive into the debate, I think it’s worth asking yourself about the purpose of homework. Most teachers use it as additional practice, or to complete assignments that began in class, but is something that a student can Google, ask their older sibling or parent, or copy from another student, more important than an assessment or assignment done in class?

Should late or missing homework be able to completely tank a student’s grade if they’re demonstrating mastery on assessments?

I’m not here to tell you how to grade. But I think that it’s worth asking yourself,

Are my grades truly working for my students and me?”

OR

Are we simply grading the way WE were graded back in the day?

Grading your grades

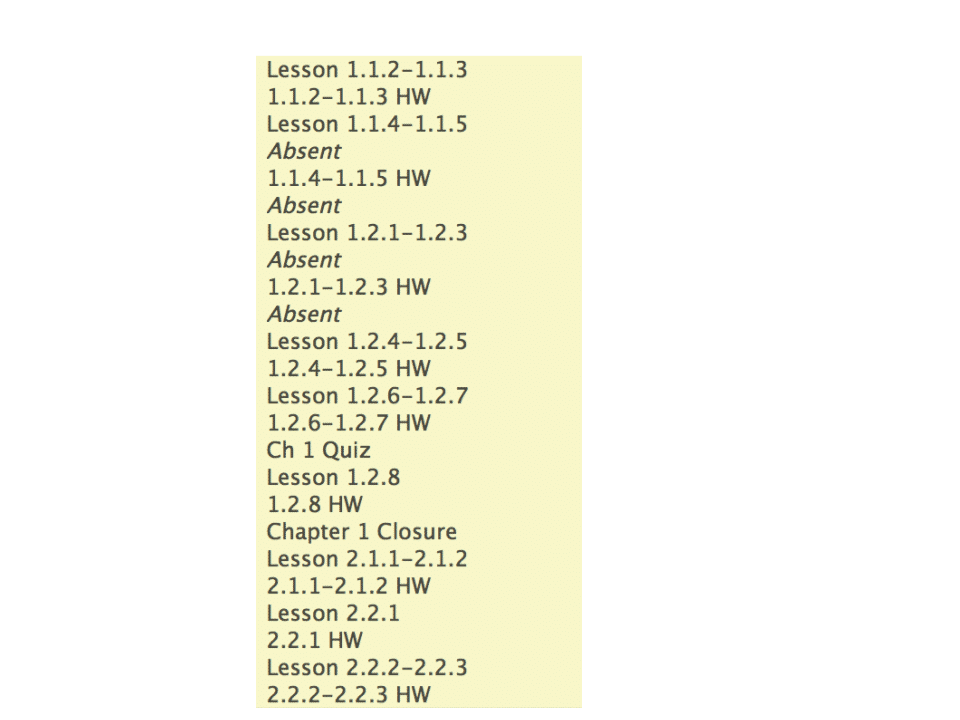

What do your grades communicate? Take a look a this example of a gradebook:

- Can you guess which subject area these assignments belongs to?

- Can you tell what standards or skills are being assessed?

- Imagine a student going back and looking at these 1st semester assignments. How many do you think he or she will actually remember?

I encourage you to go back and examine your gradebook. If possible, select a random student without looking at their name. Look at the assignments and the corresponding scores, while consider these three questions:

- What do these grades reveal about this student?

- What do these grades communicate to the student?

- What do these grades communicate to the parent/guardian?

Grading my gradebooks

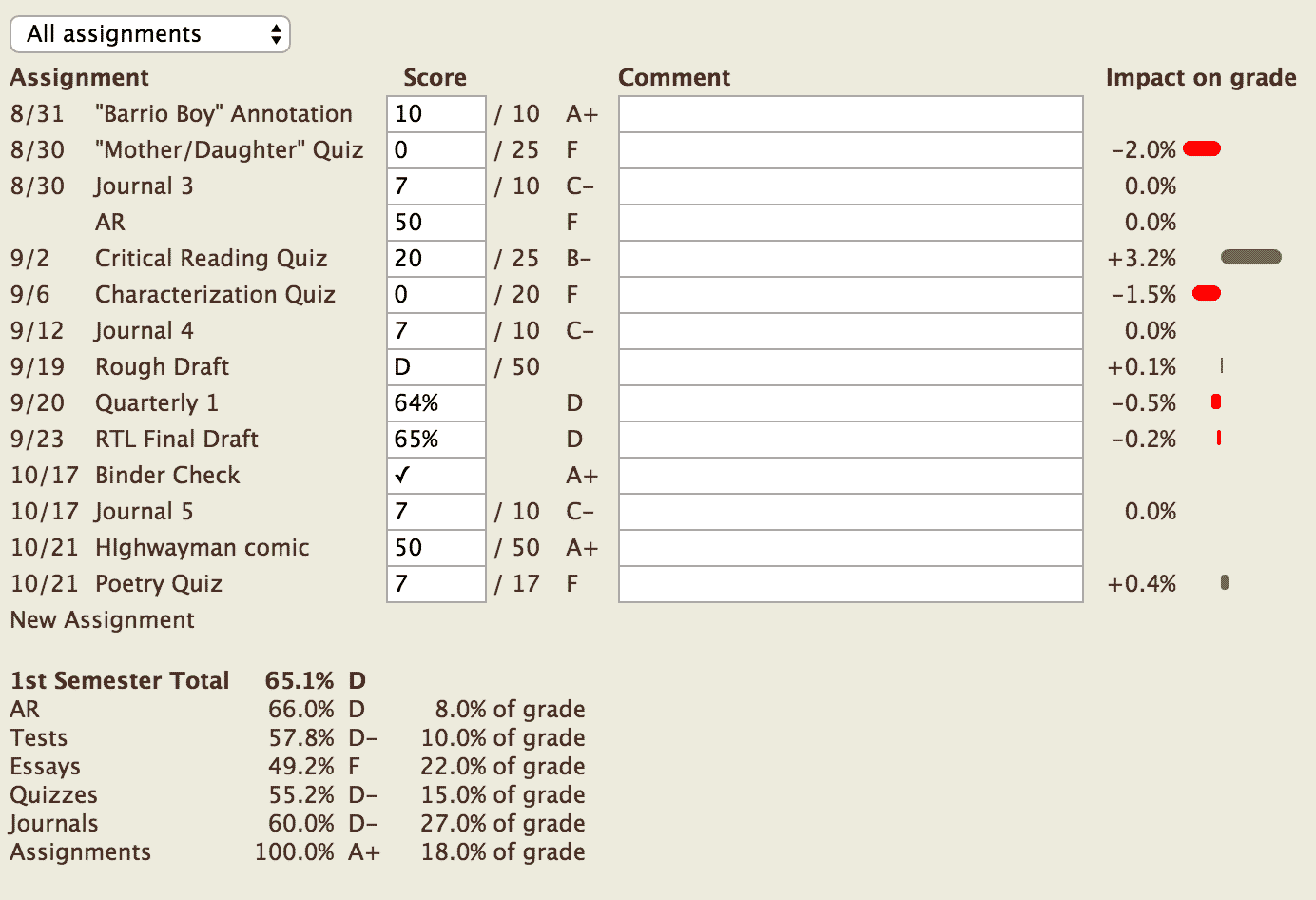

I’ll be the first to admit that my grade book was terrible in the past. Here’s a snapshot from 2011:

- Notice how this student earned A’s on the “Barrio Boy” Annotation and the Highwayman comic, which gave them an A+ for category “Assignments.”

- Look at how they earned Ds and Fs for every other category, including Tests, Essays, and Quizzes.

- If this student aced his or her assignments, but was generally failing everything else, what does that say about the level of rigor of the activities in the “Assignments” category? How much of it was teacher or group led versus individual work?

- Based on this snapshot, can you determine which skills and standards need improvement?

A lot has changed in terms of how and why I grade. Each semester I look back at my gradebook to see if I can objectively determine what the students learned, not just what they did.

Next steps

Adjust assignment names

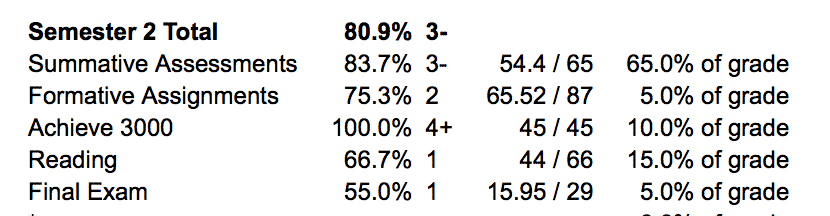

After doing this exercise, it’s time to think about possible simple changes. Even just renaming assignments to reflect the skills/standards assessed would help all stakeholders understand a student’s areas of improvement. Here’s a snapshot of last semester’s gradebook:  If a guidance counselor is meeting with a student in an effort to help them academically, clearly named assignments allow them to easily target the areas in which a student would need additional support.

If a guidance counselor is meeting with a student in an effort to help them academically, clearly named assignments allow them to easily target the areas in which a student would need additional support.

Consider your assignments categories and weights

I’m not a fan of too many categories, and I carefully weight them based on what I want students to get out of the class.  In my class, I want students to be able to read, analyze what they read, and communicate well through their writing. We do quite a big of practicing these three skills in my class, however I don’t count those attempts at mastery as much as the main essays and projects, which reflect what a student can do individually.

In my class, I want students to be able to read, analyze what they read, and communicate well through their writing. We do quite a big of practicing these three skills in my class, however I don’t count those attempts at mastery as much as the main essays and projects, which reflect what a student can do individually.

(If you’re not familiar with it, Achieve 3000 is a reading program that provides non-fiction texts for students at their personal lexile level. Therefore, reading fiction and non-fiction are both assessed.)

If you can, consider tying assignments to standards

I’m lucky enough to use an online learning management system, JupiterEd, which allows me to align assignments with their respective standards. This gives me a better picture of how students have progressed with a standard, and which areas they may need reteaching or additional support.

There are other gradebooks such as Kiddom that allow you use standards-based grading. Alternatively you can use a spreadsheet program such as Google Sheets. I previously wrote about the merits of standards-based grading, and I will reiterate that it is the clearest way to “detail students’ general academic performance.”

I hope this post gives you some ideas on how to evaluate your grading system so that it informs you as a teacher, as well as your students. The subject of grades can be contentious in some circles, but as long as you grade with intent and in a fair and consistent manner, you can feel good knowing that your practices are in place for the benefit of student learning.

If you’re serious, I suggest reading more about the topic. My go-to resources when examining my gradebook (which I do regularly) are:

How to Grade for Learning: Linking Grades to Standards by Ken O’Connor

Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessing & Grading in the Differentiated Classroom by Rick Wormeli

Formative Assessment and Standards-Based Grading: The Classroom Strategies Series by Robert Marzano

Please note that these are affiliate links, and I receive a commission at no cost to you if you purchase them. That being said, my copies are peppered with notes and Post-It bookmarks, and I stand behind them!

Yes! I overhauled my grading to a 4 point grading system that reflects academic performance in 2010 and have never looked back. I even convinced one of my old teachers (who cried, “But I WANT to grade behavior,” to do it with me. Great post!

Thanks Heather!

Great post and definitely some food for thought as I start preparing for another semester! Pinning.

Very thought provoking–especially about untimely work scores and whether or not Fs motivate.

Thanks Tara! I know it doesn’t align with the previous way of grading, but it’s something to consider!

Hello Ms. Lepre,

Thanks for sharing your reflections and evolving approach to grading. Your thoughtful approach to grading and supportive role with staff are having a tremendous impact on learning in our district.

Cheers

Dan Winters

Thanks Dr. Winters, I really appreciate the kind words!

Very informative! 🙂 Thank you!

You’re very welcome!

-Kim