Whenever someone learn that I’m a teacher, I get asked about the endless stream of grading.

I also get looks of pity whenever I tell someone what grade level I teach (Oh wow!), and then the subject (Oh you poor thing!).

It’s common knowledge that when you sign up to be a teacher (especially an English one), you’ve committed yourself to a career of staring at stacks and stacks of assignment.

Or are you?

What would you think if I told you that, after some refining, I now grade LESS but still see improvements in my students’ progress? You’d think that:

- I’m lying

- I’m a lazy teacher

- I should package the idea and sell it.

Neither of those is true (or will happen), so I wanted to share with you how I’ve accomplished this. If you’re a new teacher, I especially encourage you to read this post so that you can stop driving yourself insane.

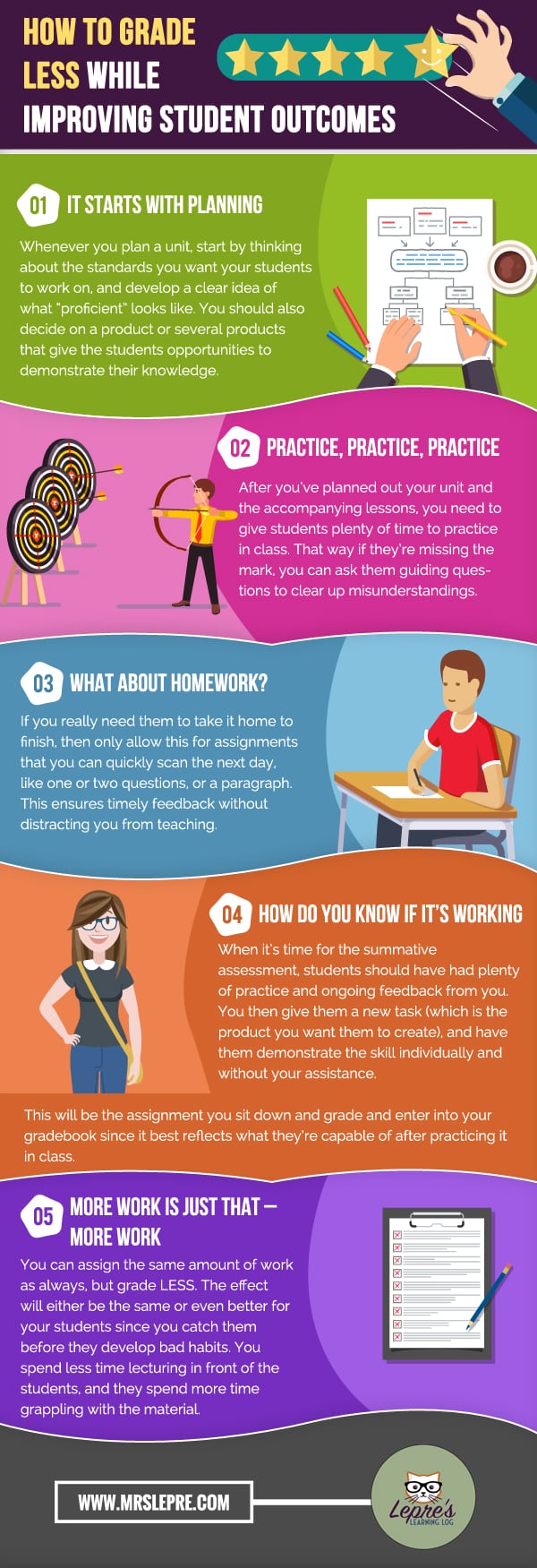

It starts with planning

Whenever you plan a unit, start by thinking about the standards you want your students to work on, and develop a clear idea of what “proficient” looks like. You should also decide on a product or several products that give the students opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge.

The key to this part of the planning stage is to not assess too many standards at once, or you’ll be overwhelmed. Yes, one can technically assess at least 5 or 6 standards in once writing piece, but

- That’s too many to grade

- That would require too much feedback that the students may not even read

- That feedback would take way too much time, rendering it useless

- It makes it difficult to reassess.

An example of how I implement this is with my first unit on writing an essay.

As I’ve mentioned before, I focus on core skills that can be applied to any text at any time. Therefore, developing their writing early on is essential.

- I start by giving a pre-assessment for the standards that involve citing evidence, using transitions, introduction, and conclusion.

- Then I teach the standards separately – evidence and transitions together (basically writing a strong body paragraph), then introduction, and finally conclusion.

- Finally, grade this assignment and give them a score so that they know their baseline level of proficiency.

Practice, practice, practice

After you’ve planned out your unit and the accompanying lessons, you need to give students plenty of time to practice in class. I emphasize doing the assignments in class because you need to be able to see them work so that you can give them instant feedback.

When I’m not teaching a mini-lesson, students are working together in groups and having academic conversations about the material. I circulate around the room and watch them write/type their answers. If I see that they’ve missed the mark, I ask them guiding questions to help clear up misunderstandings.

What about homework?

If you have them take the work home to practice, you’re leaving it up to chance. Also, you’ll have to look at it later and give feedback while they’re already working on the next step. This wastes time and creates more work for you!

If you really need them to take it home to finish, then only allow this for assignments that you can quickly scan the next day, like one or two questions, or a paragraph. This ensures timely feedback without distracting you from teaching.

Additionally, if you’re the grade-at-home type, you can have them do their assignment on a shared Google Doc, and use one of the tech tools mentioned in my webinar to give them timely feedback.

The next class period, your students will hopefully practice that same skill (but will perform better because of your feedback from the previous class), but now you’ll add another component. Lather, rinse, and repeat until you’re sure the majority of students are closer to proficiency.

The next class period, your students will hopefully practice that same skill (but will perform better because of your feedback from the previous class), but now you’ll add another component. Lather, rinse, and repeat until you’re sure the majority of students are closer to proficiency.

During this time, I may put only one assignment in the gradebook as a formative benchmark. It’s not necessary to put more, since they’re practicing in front of me and I’m assessing on the fly. Also, I don’t give grades for work done in groups or with my assistance since it’s not a true measure of their skill level.

How do I know if it’s working

When it’s time for the summative assessment, students should have had plenty of practice and ongoing feedback from you. You then give them a new task (which is the product you want them to create), and have them demonstrate the skill individually and without your assistance.

This will be the assignment you sit down and grade and enter into your gradebook since it best reflects what they’re capable of after practicing it in class.

But my students won’t care if it doesn’t “count”

You may be wondering if students won’t take class work seriously if they know that you don’t count it in your gradebook. In my experience, this never happens. However, I do allow them to work in groups the majority of the time, and because I’m circulating throughout the entire period, there’s an accountability component.

If a student is lagging or doesn’t want to work, I’ve been known to pull up a chair beside them and just watch them until they work. Eventually they’re creeped out (although I assure them that staring is caring), and they get their butt in gear. Or, during that time I’ll ask them some guiding questions so that they can get something done.

I’m not sure this will work for me

It may seem unnerving to have fewer grades in your gradebook. You may feel uncomfortable about not giving homework. I bet you think this won’t work for your subject area. But let’s just toy with the idea for a hot second and see how we can make it work for your situation.

Let’s say you’re a social sciences teacher. This probably means that you give a lot of assignments involving memorization, worksheets with questions that must be answered using the textbook, and maybe analyzing information on maps and infographics.

- Do you really need to assign a worksheet for homework, take a week to grade it with red marks across it, and then hand it back?

- What if you had them work on it IN CLASS in groups, have conversations, teach each other, and be there to address misconceptions?

- If they incorrectly answered #2 on your assignment on Mayans, rather than marking it wrong, maybe you could ask them to show you where they found that answer in the textbook. I’ll bet that as they try to find it, they’ll stumble across the correct answer!

After doing this type of activity for an entire unit where they work collaboratively and engage in ongoing discussion, you could have them use their assignments as a study guide for your summative assessment. Now you’re only grading only one or two assignments rather than five.

The biggest benefit is that this also frees up time to get to know your students’ strengths and weaknesses, which can help guide your teaching and scaffolding.

More work is just that – MORE WORK

You can assign the same amount of work as always, but grade LESS. The effect will either be the same or even better for your students since you catch them before they develop bad habits. You spend less time lecturing in front of the students, and they spend more time grappling with the material.

[bctt tweet=”The more work you decide to grade after the learning has occurred ends up being more work for you.” username=”mrslepre”]If your school or district requires that you have a certain number of grades or you must have certain assignments in the gradebook, then give them a check or check-minus as you circulate in class. If your administrator questions this, have them come in and observe you. They’ll see that visually scanning and giving feedback is the ultimate form of checking for understanding, and they’ll be more impressed with your level of engagement and individualization of your instruction.

Just try it once and see

I promise that trying this won’t result in losing instructional time. However, you may find yourself  missing the hours of grading assignments, or perhaps experience a sense of loss. Slaving away at grading may be a part of your identity, and all of that new free time may give you anxiety. However, I can suggest some light reading to fill that time, OR you could plan your next unit that involves….less grading.

missing the hours of grading assignments, or perhaps experience a sense of loss. Slaving away at grading may be a part of your identity, and all of that new free time may give you anxiety. However, I can suggest some light reading to fill that time, OR you could plan your next unit that involves….less grading.

So try it. What do you have to lose, other than the burden of hours of grading?

Ugh! Grading is probably the least desirable aspect of teaching, yet a necessary evil. Thanks for the suggestions.

I’ll be trying more in-class assessing to reduce my time with the red pen.

Hi Susan!

I completely agree! I’m glad I was able to find a way to streamline and reduce the amount of grading I have to do!

-Kim

I am a first year ELA (10th and 11th grade). I do find that I am already grading too much with little student outcome-especially when it comes to their writing skills. Can you explain further your writing pre-assessment? I would be so very grateful! And thank you for the tips!

Hi Michelle!

My pre-assessment is rather simple: I give the students a text or two to read, and then they have to write a response to a prompt using those texts as evidence. They read the texts on their own, however, prior to receiving the prompt, I have them discuss and debrief to ensure that they understand the gist of the text. At this point, I’m not assessing their reading comprehension – I’m assessing their writing. Therefore, it’s essential that they have a grasp of the text so that they will have a greater chance of hitting the key standards or skills.

Speaking of standards, prior to the pre-assessment, my PLC and I determine which 3-4 standards we want to assess. After administering the pre-assessment, we grade ONLY those 3-4 standards and generally ignore all of the other issues. While this can be difficult, we’ve found that we can better track their growth if we keep it small and simple, and just keep administering pre-assessments for the other standards.

I hope this helps!

-Kim